A few days ago, I wrote about my experiences and perceptions on how faulty reasoning, fallacies, and biases could hinder problem solving in countless numbers of scenarios in organizations (Part I).

Firstly, I wanted to explore this theme due to my bumpy journey as a consultant, and challenges I faced with exchanging specific information in project context. My expectations at the time were to minimize the number of interactions making them as productive as possible. My hopes were that “precision” (loosely defined) would allow better decision making downstream, and, ultimately, transform information into knowledge.

However, I was also on the other end of things, as a client or SME. At the time, I believe my way of conveying information was not the most logical and transparent.

By compiling this list (WIP), I wish to spark discussion and propose models to fight these very issues, and maybe, pretentiously, decrease the distance between the disciplines that study flawed logic and organizations that struggle with issues related to it.

I have now compiled Part II:

1. Functional Fixedness

Functional fixedness (FF) is a cognitive bias that affects one’s problem solving capabilities. It blocks his or her capacity to see past the traditional use of a tool or object. It makes individual creates unrealistic and unnecessary limitations that constrain the creative process and problem solving. If we expand this definition, we can think of an insurmountable number of examples, specially around machines, systems, and methods.

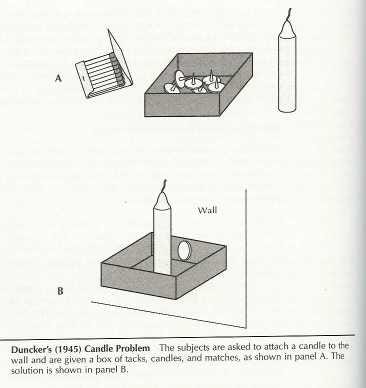

The term Functional Fixedness was coined German psychologist Karl Duncker , who conducted an experiment named “The Candle Problem”. The participants were given a candle, a box of matches, and box of thumbtacks. They were then asked to affix and light a candle on a wall made of cork in a way so the candle wax wouldn’t drip onto the table below (Picture 1).

Despite multiple attempts to achieve the intended goal, most participants failed the task. Some tried dripping wax onto the wall and fixing the candle that way, it didn’t quite work. What ultimately worked was using a thumbtack to nail one item that wasn’t initially introduced as part of the items to be used: the box of thumbtacks. Even though the object was there available and not restrictions were imposed on its use, participants were oblivious to its usefulness.

Other real life examples of Functional Fixedness are not observing that: A glass full of water (or any heavy object for that matter) can be used as paper weight, or that a key can be used as a screw driver, or that any straight object with fixed length, like a shoe or sheet of paper, can be used measure approximate distances. Cool examples of unusual applications of tools and objects are: Using an empty box of Altoids some use to keep screws, nails, etc., or this man that creates stunning art using MS Excel.

Functional Fixedness stalls creativity, and prevents people from seeing uses beyond ordinary or traditional ones. As it happens in the world, organizations display many instances of FF. The creative process or problem solving get seriously compromised when those who actively participate on it fall prey to FF.

> Product Design: Failing to see how your users might interpret design features (affordances)

- cell phone cameras can be used as mirrors.

> Software Design: Failing to see more unorthodox use cases for software

- MS PowerPoint for creating visual graphics, and reports

- MS Outlook as repository of files (sending files to yourself)

- WhatsApp allowing to send messages to oneself

Potential counter measures are (tricky one):

- Incorporate creative problem-solving exercises (ex: candle) in project context to increase awareness.

- Award for most creative solution for a problem across the business).

- Exploit “installed” creativity by setting hubs or departments focused solely on new developments, launches.

- Study how other products or services fail to cater to certain needs that might transform into opportunities.

2. Catch-all Troubleshooting

We mostly face this type of issues when trying to directly engage on solving a problem without a thorough assessment of the situation, mostly because due to resource constraints.

For these cases we jump right ahead and start “trying things out” so to provoke the expected outcome as quickly as possible, or in a less costly way.

Through a series of trials and collection of feedback, we aim at arriving to the desired state. One classic example, at least for me, is trying to troubleshoot a printer.

Most times when I use a printer is not a matter of if but when will an issue happen. On top of an error-prone device, there is poor feedback when things do not work seems to be the norm-usually an exclamation point here, or a flashing red light there.

So, with the interest of saving time, I go right ahead and attempt two things, or three things at once: I start cleaning the cartridge header, re-setting the paper in the tray, or changing the outlet used, or even the printer cable itself.

Usually, after a few tries, I end up victorious, but I don’t actually what did the trick: was it the

Next time I have this issue, I will probably repeat this whole process, why?

The reason might in the “catch-all” method I adopted. With all the changes I implemented, it becomes tricky to know what restored the condition of my printer. As an one-off way of solving something urgent, bound by time, this method might be useful, but it has very little potential long term. It does not allow for knowledge gathering, or for repetitive solutions, specially in environments where errors can cost or tolerances are narrow.

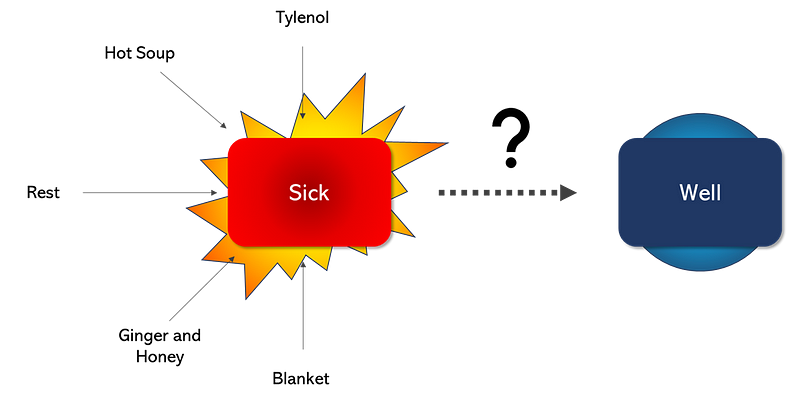

Another way to illustrate this is looking at the Tylenol-Blanket approach. When we have a cold or a flu, trying to get better as quickly as possible is the mandate. We resort on every measure at reach: Tylenol, a hot soup, or a warm blanket — amongst other things. What ends up happening is that we in fact get better but can’t later chalk it up to what did the trick.

In adopting the Tylenol-Blanket approach, we arrive to this strange place of comfort from achieving the desired outcome, and from some bitter sweet taste of not knowing what did it — like a happy accident. Was it the Tylenol ? Was it the soup? Was it both ? none ?

Another downside is that this method might lead to false conclusions. For example, we might conclude that Tylenol must be present at all costs if combinations such as Tylenol-Blanket-Soup or Tylenol-Soup-Rest both did the trick. It might lead us to conclude that we must have a “Tylenol” every time, when the soup is or that some sort of confounding effect all three had together. Once more turning our eyes into the organizations, these false conclusions might implicate in extra costs and irrational behavior to favoring with “most present factors” in place, training people on inefficient correctional procedures, so on and so forth.

Hypothetical organizational examples:

- Manufacturing setting: When trying to calibrate a machine, the maintenance supervisor try out a few settings by simultaneously tweaking three different levers at once, reaching the desired outcome, but not being able to properly document it.

- Service setting: One project manager feels pressured to release a version of a software by the end of the year. In trying to push productivity, she hires new analysts, she partners with HR to create an incentive program, and downright puts pressure of time on everyone. She able to deliver it, but when documenting lessons learned, she oversimplifies things and mentions that the pressure on her employees did it.

How to make it better?

- Map out factors (and their levels) and potential effects on the problem (example: pressure, size of the team, experience of employees, etc.)

- Outline which of these factors (x), and under which order the changes will ensue (Pressure at X psi, and Frequency at Y Hz, etc.)

- Map out possible confounding (other variables affecting your variables or your own variables affecting each other).

- Select a metric to observe the change being translated (Y) (your outcome).

- Hypothesize expected results with change introduced (what do I expect to happen and by what order of magnitude).

- Adopt changes incrementally according to roll out and observe the results through data (Y).

- Mark down outcome: was it as expected ? is the problem solved or minimized?

- Proceed with other factors until best/desired outcome is reached.

3. McNamara fallacy

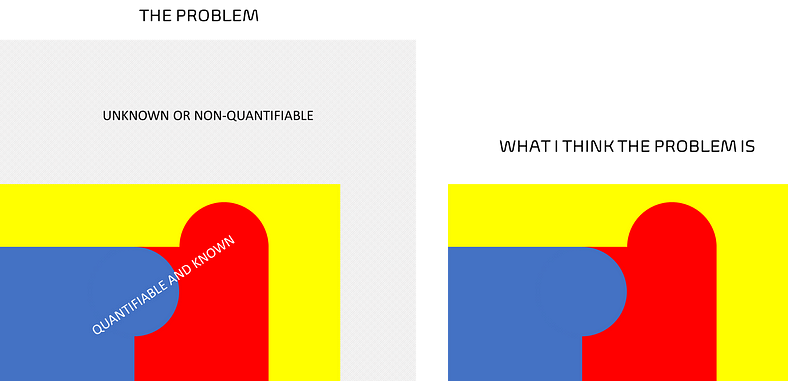

This is an interesting one. It refers to the importance of data and data knowledge to decision making. It is named after Robert McNamara, the US Secretary of Defense between 1961 and 1968, who was an avid fan of quantification and objectification.

He tried to create a model that would explain a nation’s success in war by quantifying both the volume of enemy’s body count and the nation’s own. both as a precise and objective measure of success.

Most criticized the model, because it didn’t consider a lot of elements with high dosage of subjectivity: such as feelings of the Vietnamese rural population. When told about this by US Air Force Brigadier General Edward Lansdale, McNamara wrote it down on his list in pencil, then erased it and told Lansdale that he could not measure it, so it must not be important.

The dismissal came basically from the realization of the subjective nature of measuring that, and then equating that complexity with lack if importance. The major problem is then giving disproportional importance to what is available and quantifiable, dismissing or deeming unimportant what is not. In Argumentum Ad Ignorantiam — the flawed rationale “If I don’t know it, it doesn’t exist, does not happen, or it’s not important.

In companies, this is more recurrent than we think:

- Prioritization Exercises: While trying to analyze a portfolio of potential projects that would then be shortlisted to a roster of projects for that year, I have heard that we should not consider the number extra-departmental resources needed to implement that said project under the complexity category because it was simply too hard to measure.

- Brainstorming Sessions: This is another type of dynamic that brings the fallacy to life. Not all, but there are many instances which the “unknown” quickly becomes “unimportant” — “oh we do not it happens, so probably it does not” or a more seasoned employee who “has seen it all” disagrees with another new one who witnessed that in their work environment in the first weeks in the new job.

A few turnarounds for this is

- Incentivize an open minded discussion.

- Detach information complexity from importance.

- Be mindful of real constraints smoke screen the responsibility of “knowing things”-time, resources, and cost can prevent things from being probed, but that should be mistaken with “it doesn’t happen”

- Rely o caveats: …haven’t seem but assume it can happen…

- Study the Cynefin Framework

I sense that faulty reasoning-illustrated by the above and more-is in part to blame for poor collaboration, and it sets booby traps all over the place. It places pitfalls in organizations to deliver value that are either not seen or shrugged off in the name of “speed”.

It forces endeavors backwards, like the unnoticed air the car resists a driving car, and materializes when we look at the “fuel consumption” in projects, like time to delivery, deviation from cost, unplanned disbursement, so on and so forth.